Death, disaster and redemption - England's tumultuous tour of India

Sign up for notifications to the latest Insight features via the BBC Sport app and read the latest in the series here.

Peter Baxter had just got to much-needed sleep when he was startled awake.

It was still dark outside, but the phone next to Baxter’s head in his Delhi hotel room was ringing, loudly and insistently.

Baxter had only arrived in the city a few hours earlier. As Test Match Special’s producer, he was in India to cover the England men’s team’s tour of the country.

As he blearily lifted the receiver and listened to the voice on the other end though, it was the start of an assignment that would test him, and the team he was following, in ways they could never have foreseen.

The tour began on Halloween – 31 October 1984 – and continued until early February the following year.

In those three months, India would be convulsed by political assassinations, sectarian turmoil and an industrial disaster that rivalled Chernobyl in its loss of life and lasting ecological damage.

Yet, through the turmoil, the tour stayed on the road, taking in 16 venues, 12 first-class matches (including five Test matches) and six one-day internationals (ODIs) from Guwahati in the north-eastern Assam region of India, to Colombo in Sri Lanka, via all compass points in between.

On several occasions, the tour looked certain to be cancelled only to be resurrected. By the end of it, a young, inexperienced England team under the captaincy of David Gower would do what no other England team had done before, and only one has managed since: come from behind to win a Test series in India.

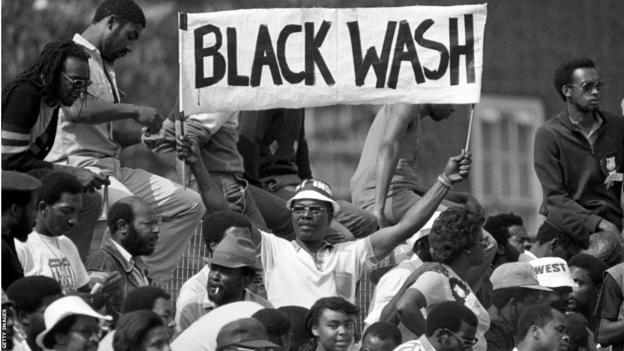

England’s form in advance of the tour was patchy, at best. They had been trounced 5-0 by the all-conquering West Indies in a home Test series and were sorely missing key players, such as Graham Gooch, Bob Woolmer and John Lever, who were still banned after defying a sporting ban and embarking on a rebel tour of apartheid South Africa in 1982.

While India could not match the depth of the West Indies at that time, they were a very hard side to beat in their own conditions. Three years previously, a first-choice England had suffered a 1-0 series defeat in a six-Test tour. The now-banned Gooch was their top scorer.

Ian Botham was not banned. However England’s greatest all-round cricketer had opted out of the tour of India.

The previous winter in New Zealand, tabloid editors had deployed news reporters to track Botham in the very reasonable hope of uncovering salacious stories that might dominate the front, rather than back, pages. Botham was a superstar and stories about him, especially scurrilous ones, sold papers. Botham decided to take a break from cricket rather than endure similar in India.

Without him and the rebel tourists, England were forced to select a hotch-potch of young, largely untried players (Richard Ellison, Chris Cowdrey, Neil Foster, Tim Robinson, Norman Cowans and Vic Marks) alongside a pair of experienced, if eccentric spinners (Pat Pocock and Phil Edmonds), a couple of familiar faces (Graeme Fowler, Allan Lamb) and a leadership group that consisted of languid, laid-back captain Gower and his hitherto underperforming vice Mike Gatting.

It was a squad that arrived in India with a little hope, but no expectation.

The team, fresh off the plane, was soundly asleep when news began to spread that Indira Gandhi – India’s Prime Minister, the daughter of the country’s first post-colonial leader and the dominant figure in Indian politics for nearly twenty years – had been shot by her Sikh bodyguards.

As the players slept, Baxter awoke.

“As soon as I shut my eyes the phone was ringing,” he says in Test Match Special’s three-part podcast on the tour.

“It was the BBC newsroom in London, saying ‘it’s about this Gandhi business’ and I said ‘what Gandhi business?’ So they had to tell me. Unfortunately the BBC’s man in Delhi was out of town following Princess Anne, who was visiting up country.

“So they asked me to get down to the BBC office to help his assistant – Satish Jacob – put endless reports on the Today programme initially and then on other news programmes.”

It was down to Baxter – more used to the gentle pace of a Test match – to verify whether or not one of the world’s most recognisable and influential politicians was alive or dead.

“Satish was getting phone calls and the telex machine was chattering away as well,” remembers Baxter.

“Eventually a call came through from somebody Satish knew saying Mrs Gandhi is dead. I was conscious of the BBC’s dictum that you must always have two independent sources before you announce something like that.

“And a few minutes later, we got a telex message saying the same thing. I consulted Satish, who was a bit nervous about announcing it. So I told the news desk in London that we were getting the news that Mrs Gandhi had died but that I was looking for a bit more authority than this. The desk said. ‘Well, if you’re happy with that old boy, go for it.’ So I announced it.

“I was a bit worried later to find that it hadn’t been announced in India at all anywhere.”

Prakash Wakankar – now part of the Test Match Special commentary team – was celebrating his 21st birthday over lunch in a restaurant in Pune when he first became aware that trouble was afoot.

“Suddenly the owner, who was a Sikh gentleman, came around to all the folks who were sitting in the dining area and said ‘you’ve got to leave. I’m shutting down’. He said there is news that Mrs Gandhi has been shot and there’s a danger of riots,” Wakankar remembers.

“It was a very strange situation. The city came to a grinding halt. The news started filtering of some of the horrible stuff that was happening in Delhi.”

Violence spread across the country from the capital, with nearly 3,000 Sikhs killed by Hindu mobs over three days of violence.

“So many different things were happening around that time,” adds Wakankar.

“It was a tough, tough period for a lot of people and it sort of tore apart the fabric between the Hindu and the Sikh communities, which was something which we never ever imagined.”

By late morning, the England players were gradually making their way to breakfast in the team hotel and finding out the news.

“Gandhi was shot only about two miles from where the hotel was and there were fires billowing up. Our imaginations started to wander and think, well, what’s going on here?” remembers Marks.

The British High Commission advised no one to leave their hotels, but after a few days locked down the tour party was becoming restless.

“The players were asking ‘What are we doing here? How long are we going to stay here?’ says Marks.

“It was tough. It was a very young touring party, a lot of new tourists, so it was a fairly traumatic start for them.

“We wanted to have a word with our manager Tony Brown, who could be quite a forceful individual. So we had this stormy meeting in which Allan Lamb was really quite adamant that we shouldn’t be here, that we should be going home.

“Brown, who had charge of all our passports, brandished Lamb’s passport and said ‘well, here it is if you want it, you can take it and you can go home if you want to’, which was quite a moment.”

With no-one willing to be the first to jump ship, the tour stayed on track, admittedly with a switch in location.

As India was now plunged into a 12-day period of official mourning, with no prospect of playing matches or even having access to facilities on which to train, England jumped at the offer of leaving the country on the Sri Lankan president’s plane and heading to Colombo for a hastily-arranged first class fixture, followed by an ODI.

While the cricket in Sri Lanka was uneventful, the detour brought the players and travelling press pack closer. The ODI was rained off after 38 overs, and, with the outfield under water, Baxter trotted off to conduct his post-match interview with Gower in the team’s changing room.

“Even the changing room was underwater so Gower said to me probably the best place to go is the bathroom, which is a little bit drier,” remembers Baxter.

“So we did our interview there and thereafter for the rest of the tour, David would always say to me if we wanted an interview, let’s find a bathroom.”

“We spent a lot of time with the press in a way that wouldn’t happen now,” says Marks. “You’d be on the same bus, you’d go to the same bar and a lot of friendships were made. We were all in it together.”

Within a week of heading for Sri Lanka, astonishingly England were back in India. A rearranged schedule jammed in three first class warm-up matches in 12 days, travelling from Jaipur, to Ahmedabad to Rajkot.

The middle of the three matches was against an Indian under-25 XI which featured two players who would come to dominate England’s thinking across the upcoming Test matches; an 18-year-old Laxman Sivaramakrishnan picked up five wickets with his leg-spin, while Mohammad Azharuddin scored 151 as the under-25s won by an innings. Both players were as yet uncapped by India but that would soon change.

England travelled to Bombay, now Mumbai, to prepare for the first Test. The day after their arrival in the city they were entertained for the evening by Percy Norris, the British Deputy High Commissioner.

Such functions were a regular and often tedious chore for touring sides but Marks remembers this one differently. “It was a small affair in his flat,” he says. “Norris obviously knew his cricket. He was relishing the event. It wasn’t a duty call for him and we all remembered having a really great time.”

The following day the tour party gathered for a team photo to be greeted by the news that Norris was dead.

As he was driven to his office through the city’s congested centre in a distinctive white Rover, two gunmen had opened fire. A group calling itself the Revolutionary Organisation of Muslim Socialists claimed responsibility, saying that Norris was a British spy with close links with the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and that India’s old colonial rulers were continuing to interfere in the country’s politics.

There was no suggestion that the killing was linked to Gandhi’s assassination, but once again the tour was in peril.

“He was English and we were wondering why was he under threat?” remembers Marks. “Why would this happen to him? It was a cumulative effect. With what had happened at the end of October and now we’ve got our Deputy High Commissioner, who we have got to know the previous evening, being assassinated. Most people thought ‘well, we’ll be going home now'”.

Why England didn’t leave remains something of a mystery. Perhaps the proximity of the first Test, due to start the next day, had something to do with it. Marks though attributes the decision elsewhere.

“David Gower and Mike Gatting did a kind of quick tour of the rooms to canvass opinion,” he remembers. “To our amazement Gower said, ‘right, we’re going down to the nets to practise.’ To which dear old Graeme Fowler piped up with ‘What? Target practice?’

“We thought we’d be going home, that that would be it as far as this tour was concerned. But the powers-that-be thought otherwise.”

So the Test match went ahead and the series began. England started brightly before Fowler was out caught and bowled by Sivaramakrishnan, the mystery leg spinner who had troubled them 11 days before, and was now making his debut.

Marks detected that the players’ mindset was, unsurprisingly, not right after all the turbulence and violence of the last few weeks and days.

“Fowler hit a high full toss back to Siva and I remember him saying afterwards that, having got out, there was just a scintilla of relief that he was no longer exposed in the middle.

“There was still that unease. He felt he’s the English opening batsman and quite a prime target.”

Clearly Fowler’s ‘target practice’ jibe was not entirely in jest.

India dominated the match, bowling England out cheaply and then, thanks to hundreds from Ravi Shastri and wicket keeper Syed Kirmani, gaining a lead of 270.

Despite their eventual heavy loss, there was a crucial silver lining for England. Gatting, in his 54th Test match innings, finally made his first hundred. Averaging just over 24 going into the series, he was a controversial selection who had frustrated England fans with unfulfilled promise.

Marks attributes Gatting’s new-found form to astute man management.

“They made him vice captain,” Marks says. “So Gatt suddenly goes from a slightly peripheral, exasperating talent to the main man who’s going in at three. He’s the Sergeant Major to David Gower and suddenly he’s got confidence. This innings cemented that.”

The fact remained though that England were 1-0 down in India. Teams don’t come back from that, let alone a young, inexperienced and traumatised one. In addition, Sivaramakrishnan had picked up 12 wickets in the first Test with only Gatting looking capable of surviving against him.

Events off the pitch continued to overshadow the series as well. On the last day of the first Test, news filtered through of a disaster unfolding in Bhopal, a city in the centre of India.

The Union Carbide chemical plant, which manufactured the highly toxic gas methyl isocyanate, was leaking. A deadly fog enveloped the city and, in the days and weeks to come, it became clear that India had suffered the worst industrial disaster in history.

“Bhopal is probably as close to an atomic disaster that that one could ever have”, says Wakankar. “A repeated occurrence of minor accidents had created a situation which was a tinderbox. It was just waiting to happen. And finally it did on that fateful night. Its effects remain to this day.

“You can walk through that area of Bhopal and you will see physical evidence in the shape of people who’ve been affected, multiple generations, young children, deformities.”

The Indian government says some 3,500 people died within days of the leak and more than 15,000 in the years since. Campaigners put the death toll as high as 25,000.

Still, incongruously, the tour continued.

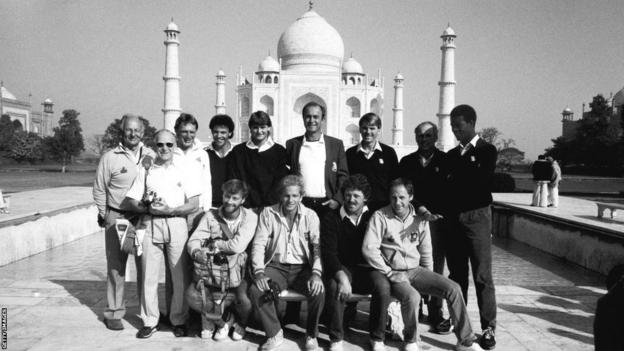

Looking at the pitch, the expectation was that the second Test in Delhi would be a short match, dominated by spin. India’s captain Sunil Gavaskar even advised a journalist to plan a trip to the nearby Taj Mahal for the fourth or fifth day. So when India won the toss and batted, English hearts sank.

The home side compiled a competitive 307 in their first innings but when England batted, the predicted disintegration of the pitch never materialised. Instead, thanks to a masterful 160 by opener Robinson – his first Test hundred – the tourists secured a lead of 109.

Time, though, was running out. By the end of the fourth day, India had crawled to a lead of 19 with just two wickets down, and their legendary captain Gavaskar was still at the crease. By lunch on the fifth day, the lead had nudged beyond 90. A draw loomed and England were getting frustrated at a potential missed opportunity.

Marks remembers a rather fractious scene: “Gower, who is the most laidback man of all, actually got quite angry because he sensed that there was a sort of element of resignation. He got quite stroppy with everyone and said ‘Come on we can do this.'”

And do it they did, albeit with a bit of help from star Indian all-rounder Kapil Dev. Kapil was under orders not to play any of his trademark attacking shots until the draw was secured. The orders fell on deaf ears. After smashing Pocock for six from one of the first deliveries he faced, Kapil holed out to Lamb in the deep on the seventh. His dismissal triggered a collapse.

India lost their last six wickets for just 28 runs leaving England with just 125 to win in two hours. Had India batted another 20 minutes they would surely have made the game safe. Instead, England romped to their victory target in just 23.4 overs with time and eight wickets to spare.

From frustrated resignation at lunch, England were victorious four hours later and unbelievably the series was level at 1-1.

Bitter recriminations followed. Responsibility for India’s defeat was placed squarely on Kapil’s shoulders. Remarkably, India’s greatest all-rounder was not just pilloried, but found himself dropped from the next Test match in Calcutta, now Kolkata.

From a seemingly hopeless position, England were level and the Indian camp was tearing itself apart.

The third Test match was an abysmal game, played out on an unresponsive surface. Gavaskar chose to bat first and in between breaks in play for mist, fog and drizzle, he kept England in the field until after lunch on the fourth day. So tedious was the on-field action that England spinner Edmonds took to reading a newspaper upside down in the outfield while the Indian batters grinded away.

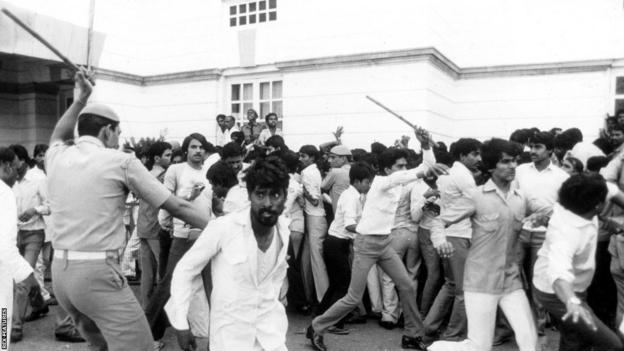

The crowd was incensed. Blaming Gavaskar for the lack of ambition and infuriated that their swashbuckling hero Kapil had been omitted, they hurled fruit and insults at the Indian captain.

The game petered out into an inevitable draw, so the teams headed South to reconvene in Madras, now Chennai, for the fourth Test with the series still level.

After the debacle at Calcutta, India made changes, bringing back Kapil and calling up dashing opener Krishnamachari Srikkanth as they looked to up the tempo of their cricket. England too made a crucial change, bringing in tall Essex seamer Foster in place of Ellison.

What unfolded was the exact opposite of the torpor in Calcutta.

“India were batting first but lost wickets really quickly to Foster and Cowens, and were 45-3 at one point,” says Marks. “There was a partnership between Amarnath and Azharuddin, but it was 21st century stuff.

“They’re scoring very, very quickly on a lovely wicket. There’s pace in it and you can play your shots. And they played a lot of shots, but they also kept getting out. The nicks were carrying. It was highly entertaining.”

Had India been spooked by the reaction to the dropping of Kapil? Had England got in their heads? Either way they were bowled out well before the end of the first day for a sub-par 272 with Foster taking 6-104.

Quite how good the wicket was become apparent over the next two days as England amassed the eye-watering total of 652-7, thanks to Fowler and Gatting both scoring double hundreds. Never before in Test history had two Englishmen scored double hundreds in the same innings. Their partnership of 241 took England out of sight.

Marks got a good view of proceedings in between taking drinks out to the middle. “Foxy [Fowler] played with considerable restraint to start with,” he says. “He bided his time. He didn’t play too many exotic shots initially, but gradually he started to go over the top. Siva in particular started to wonder where another wicket was going to come from.”

Sivaramakrishnan had taken 18 wickets in the first three innings of the series. By this, the fourth Test, his figures were a miserable 1-145. England had unravelled the mystery.

Taking to the field with a first-innings lead of 380 and with plenty of time left in the game thanks to India’s attacking approach, victory was just a matter of time.

England had turned the series around to lead 2-1 and were now within touching distance of an unprecedented victory.

With one match still to play and India now desperate for a series-levelling win though, the final-Test pitch in Kanpur would surely play to the hosts’ strengths.

“We’re convinced it was going to be a stitch-up”, remembers Test Match Special’s Jonathan Agnew, who had joined the touring party in Calcutta after Paul Allott had to return home with a back injury.

“But it wasn’t”, says Marks. “There was a rumour going around that the groundsman had a cousin who was quite a good cricketer, who Sunil Gavaskar had never taken any notice of and never selected. This was his vengeance. He was going to produce a flat wicket.”

The extent of the truth behind the rumour was unclear, but to England’s delight the pitch was flat and hugely favoured the batters.

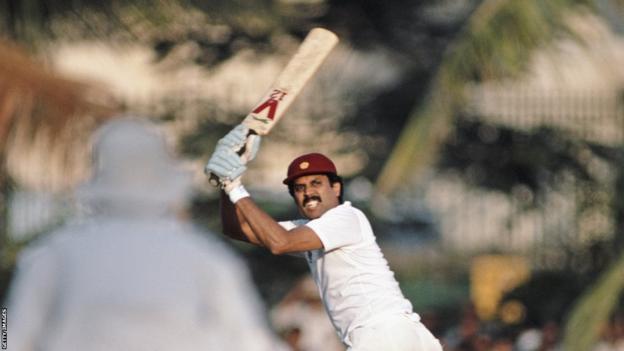

Azharuddin scored yet another hundred, his third in consecutive Test matches and fourth overall against England that winter, as India made 552-8. Despite a brief wobble when England lost their sixth wicket still 68 runs shy of avoiding the follow-on, a partnership of exactly a hundred between Edmonds and Gower, playing a captain’s knock at just the right time, steered England to safety.

“Gower had underperformed by his standards in the earlier Tests,” says Marks, “but he had a terrific tour as captain. This was his team for the first time, really. He was the one who brought back Phil Edmonds, who bowled a lot of overs and got enough wickets to win the series. So it was quite fitting that Gower and Edmonds got us over the line.”

England were eventually bowled out for 417 deep into the final day, but there wasn’t enough time for India to force the win. England had the draw that secured a historic series victory.

A Test series that initially looked like it wouldn’t last a week, was over after 98 fraught, frantic, and occasionally frightening and sad days on tour.

.jpg)